Section 2 | Anthelmintic Resistance in Sheep & Goats

Industry

Page 08 /

Identifying GIN Infections in Your Herd/Flock

In addition to the clinical signs listed on the Overview of Gastrointestinal Nematodes (GIN) page, there are several ways GIN can be identified in your herd or flock.

Fecal Egg Counts

Diagnosis of GIN parasitism is done by collecting manure samples from animals that are grazing pasture and examining the feces under the microscope to determine if eggs are present. Fecal analyses can help with:

- Evaluating parasite burden to decide if treatment is warranted

- Detecting and monitoring infections in healthy-looking animals and making a diagnosis in sick animals

- Choosing the best medication that targets the specific parasite present

- Determining the effectiveness of a treatment

- Take a sample prior to treatment and a predetermined period after treatment

Unfortunately, there are limitations to fecal egg counts. Counts are greatly influenced by the season in which the samples were taken, as well as the species of parasite that is suspected to be present. Other tools that can be useful in diagnosing gastrointestinal parasitism includes the Five Point Check system.

The Five Point Check System

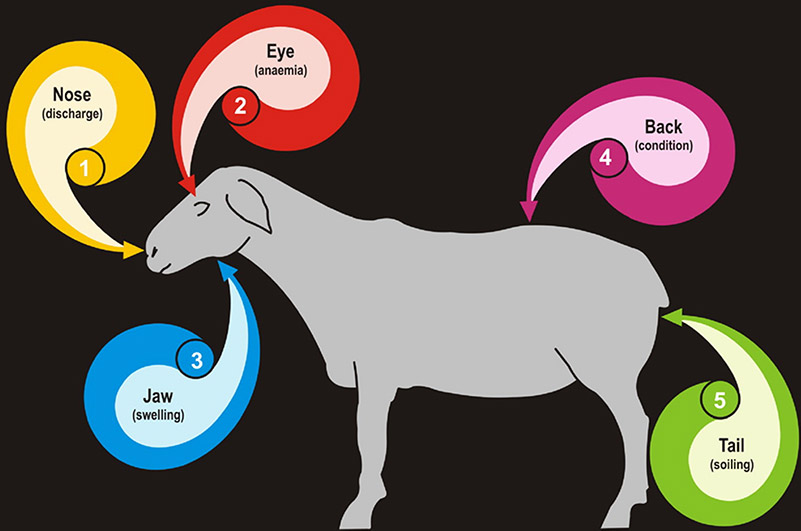

The Five Point Check is a systematic way to examine and evaluate signs that are present when a parasite is affecting a small ruminant species. It involves monitoring the nose, eye, jaw, back or topline, and tail in a systematic manner to identify those animals that may require targeted treatment with an anthelmintic1.

Figure: The Five Point Check System1

Nose (Nasal Discharge)

Although not a clinical sign that is always representative of a GIN infection, nasal discharge could indicate an infection with other parasites such as nasal bots or Oestrus ovis. This is not a sign that is specific to parasites. It could also be present with respiratory disease and/or pneumonia. Hence, it is important to rule out other causes prior to treating animals only displaying signs of nasal discharge.

Eye (Anemia) – FAMACHA Scoring

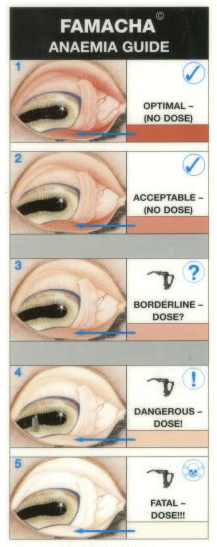

For the barber pole worm, Haemonchus, an incredibly important indicator for its presence is anemia – your sheep or goat will be pale, lethargic, and weak because of blood loss. This can be monitored using the FAMACHA scoring system, where individual animals are scored according to the appearance of their ocular mucous membranes (the fleshy portions of the inner eyelids) every 2-3 weeks. This is normally done when Haemonchus is a problem in the herd/flock. FAMACHA score cards can be sent to producers after they have completed an online training module. For more information, visit Ontario Sheep.

It allows for a deworming approach targeting only those animals that are affected with Haemonchus. Animals that are a score of 1 and 2 do not require treatment, whereas those with a 3 should be monitored closely. If an animal scores a 4 or 5, it should be treated immediately with an anthelmintic, as it is clinically anemic2.

Source: University of California

Jaw (Swelling)

Most GIN parasites will feed on protein. In severe infections, protein levels can drop to very low levels. When protein levels are low, blood vessels will leak out fluid which gathers under the skin producing a swollen area under the jaw termed “bottle jaw”. This clinical sign indicates that advanced disease and a heavy worm burden is present.

Source: Shepherd’s Notebook

Back (Body Condition Scoring)

When animals are within a group that is in a similar production stage, they should have a similar body condition score (BCS). It’s assumed that the body condition reflects the level of nutrition, feed efficiency and conversion, as well as the demands on the animal given its production stage, such as growth, pregnancy, or lactation. However, if the condition score varies by more than one unit score within a particular group, there might be a chronic disease at play in the group (e.g. gastrointestinal parasitism). Groups should be relatively uniform, given that they are managed in the same way.

There is a long list of factors that could impact condition loss causing variation. These additional factors (e.g. poor pasture, coccidiosis, pneumonia, Johne’s disease) need to also be evaluated as well. Work with your veterinarian to rule in or out different potential causes of non-uniform production groups.

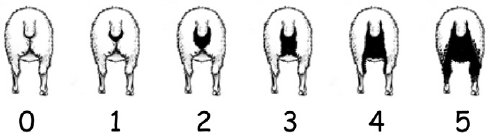

Tail (DAG scoring) in Sheep Flocks

Some parasitic infections cause diarrhea. DAG scoring is a way to objectively evaluate the number of animals in your flock that have diarrhea. When animals have diarrhea it will cling to the wool. DAG is fecal contamination of the wool surrounding the tail and hindquarters. These animals are at risk of developing flystrike, where flies lay eggs on skin or wool contaminated with manure. These eggs will develop into maggots that can infect the skin and wool of the affected area.

Similar to some of the other signs in the Five Point Check, other factors can influence the fecal consistency of the animals including diet, stress, and other pathogens.

Source: Sheep Improvement Limited

Final Note on GIN Diagnosis

Monitoring your flock for signs of parasitism is a requirement as per the Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Sheep. The Five Point Check and fecal egg counts are examples of ways to determine if your flock is affected by parasitism. Work with your veterinarian to determine the best strategy for managing the risk associated with parasites in your herd/flock and strategically deworm to preserve the use of deworming medications for future use.

References

- Bath, G.F., and J.A. van Wyk. 2009. The Five Point Check for targeted selective treatment of internal parasites in small ruminants. Small Ruminant Research. 86:6-13.

- Fleming, S.A., T. Craig, R.M. Kaplan, J.E. Miller, C. Navarre, and M. Rings. 2006. Anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal parasites in small ruminants. J. Vet. Intern.

Med. 20:435-444.