Section 2 | Anthelmintic Resistance in Sheep & Goats

Industry

Page 07 /

An Overview of Gastrointestinal Nematodes

Parasitism is a significant health issue in sheep and goats worldwide. Specifically, gastrointestinal nematodes (GIN) or worms are a source of significant illness and production loss in the industry. In Ontario, it is common to identify many types of GINs including Teladorsagia (brown stomach worm), Haemonchus (barber pole worm), and Trichostrongylus1 (small stomach worm). Animals infected with GIN show signs that can include2:

- Poor milk production

- Reduced feed intake and feed efficiency (they don’t gain weight as well)

- Weight loss

- Reduced wool production

- Anemia (low red blood cell levels)

- Lethargy

- Diarrhea

These GIN can cause a lot of damage. Currently, these parasites have developed widespread resistance to many of the main classes of dewormers (otherwise known as anthelmintics). This means that these products are less effective at killing parasites. These resistant parasites continue to survive and cause damage despite treatment with these drugs. Hence, prudent use of anthelmintics and other management strategies need to be implemented to maintain the effectiveness of these medications and slow the development and spread of anthelmintic resistance.

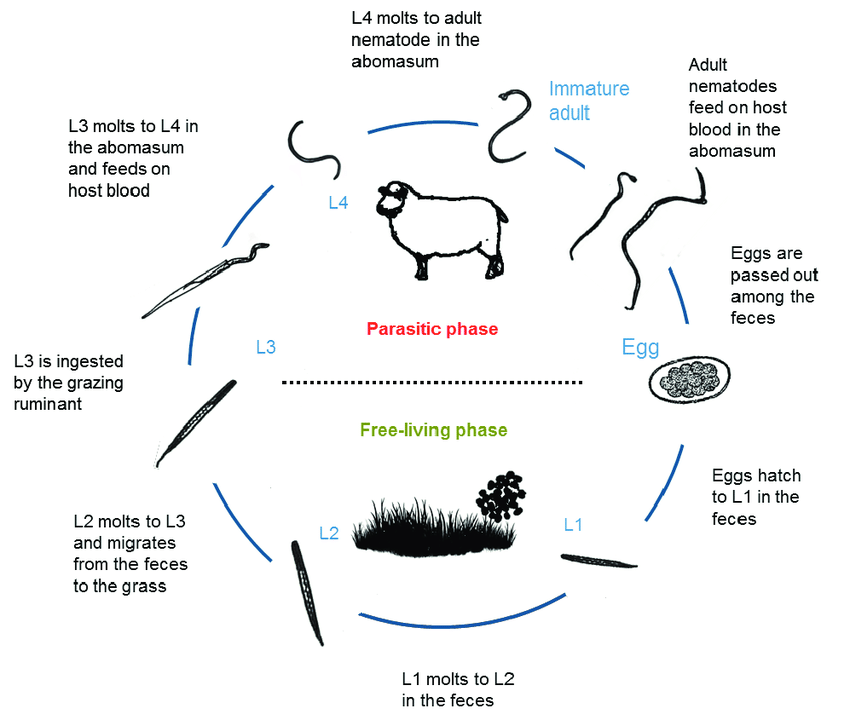

GIN Life Cycle

All nematodes have 4 larval life stages. Sheep and goats get infected by grazing on pasture contaminated by feces containing the ‘infective’ larval stages. Eggs are shed by an infected animal in their manure. These eggs hatch and the nematodes progress through the first 2 larval stages (L1, L2) by feeding on bacteria within the fecal pellet. At the third larval stage (L3), the larvae move onto blades of grass in the pasture so that they can be consumed by unsuspecting grazers – L3’s are the ‘infective’ larvae (they are the stage that causes disease). This migration up the grass requires the right environmental conditions. The climate must be warm, moist, and humid. L3 will remain on the herbage until eaten. Once the L3 is eaten, the parasite will develop into the L4 stage, and subsequently develops into an adult stage. It’s the adult parasite that causes disease and lays eggs in manure. The figure below describes the lifecycle of these nematodes.

Figure: The life-cycle of GIN3

In the winter, GIN undergo a period of arrested development in infected adult hosts until environmental conditions are ideal again (warm, moist, and humid). Also, when ewes and does approaching kidding and lambing time, their immune system becomes relaxed. This results in an increase in eggs passed in the feces a few weeks before giving birth until approximately 8 weeks later. Therefore in the spring, these adult sheep and goats shed early larval stages and are the primary source of infection for younger animals. As the season progresses through the summer, youngstock will become the greatest contributors of shedding eggs on pasture.

Effects of GIN on the Host

GIN will have their impacts on either the abomasum (the stomach) or small intestine depending on the species. Adult worms will burrow into the lining of the gut and destroy the tissue. This can cause protein and blood loss and the inability to absorb nutrients. This damage to the intestinal tract is what leads to significant production losses attributed and clinical signs associated with intestinal parasites.

Source: Dalhousie University

For more information on intestinal parasites of small ruminants, and how to manage parasites on your farm without relying on anthelmintic medications, take a look at the Handbook for the Control of Internal Parasites in Sheep & Goats

References

- Mederos, A., S. Fernandez, J. VanLeeuwen, A.S. Peregrine, D. Kelton, P. Menzies, A. LeBoeuf, and R. Martin. 2010. Prevalence and distribution of gastrointestinal nematodes on 32 organic and conventional commercial sheep farms in Ontario and Quebec, Canada (2006-2008). Veterinary Parasitology. 170:244-252.

- Mavrot, F., H. Hertzberg, and P. Torgerson. 2015. Effect of gastro-intestinal nematode infection on sheep performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit. Vectors. 8:557.

- Engström, M.T. 2016. Understanding the bioactivity of plant tannins: developments in analysis methods and structure-activity studies.

- Handbook for the Control of Internal Parasites in Sheep & Goats (2019) https://www.ontariosheep.org/uploads/userfiles/files/Parasite%20Handbook_April_2019%20updated_reduced.pdf